Greetings fellow wargamers! Recently, in my latest attempts to put off painting Blackstone Fortress or the small handful of elite units I’d need to make my Skaven army remotely feasible on the tabletop, I decided to paint a warband for the venerable Games Workshop Specialist Game, Mordhiem – in best keeping with the style and tone of the game as I could. In an attempt to keep the length of this blog post within reason, I’ll be breaking it up into two (or more) parts – one on my motivation for doing this, and another about the building and painting of said warband – so let’s get to it!

Those of you who follow this blog are probably aware of my fondness for a largely bygone age of Games Workshop ruleset design. It’s why I’m so partial to The Horus Heresy, and a has a lot to do with why I play the Middle-earth Strategy Battle Game. Variety – the spice of life – has something to do with it as well. When compared to the largely similar Age of Sigmar and 8th Edition Warhammer 40,000, both the Horus Heresy and Middle-earth SBG feel like their own games; and in an era where each of these ‘flagship’ games are so similar to one another1, I find it refreshing and engaging to be able to switch things up a bit. Still, I can’t deny that there’s a bit of rose-tinted nostalgia influencing things as well – I like that these games play more like the Warhammer that I grew up with. They still feel that much more familiar to me than the ‘modern’ approach of Games Workshop’s current flagship games. But it’s not just the rules that feel so faithful to the Games Workshop of yore, it’s the setting and tone of them as well. This is likely due to both games representing a set period in the fluff (the Horus Heresy and the 3rd Age of Middle-earth respectively), with a little less ‘wiggle room’ for reinvention. After all, it’s not as if Games Workshop can have Sauron blow up Eriador or introduce Primaris Marines to the 30K setting, right?

Maybe it’s just me, but it feels like ever since the Age of Sigmar and Dark Imperium, Games Workshop has been trying to pivot away from the morbid aesthetic that originally drew me to the setting – in favour of something a little more slick and refined. Of course, I’m not trying to suggest that a change of direction in Games Workshop’s games, art and lore is by any means a new thing. For as long as I’ve been involved in the hobby, the Warhammer Fantasy and 40,000 universes have had plenty of variance in their predominant art styles, use of colour and overall tone. Indeed, just before my time in the hobby was the (tragic, if) now iconic Red Period, where everything looked… very colourful. This period was of course superseded by the wonderful, desaturated and actually, still pretty red Grimdark aesthetic that I like to harp on about so often. This aesthetic I think is hugely synonymous with Warhammer 40,00 3rd Edition, but it found it’s way into Warhammer Fantasy as well by the time 6th Edition came into play.

But time marches ever onward. As technology has improved, so has print quality and the proliferation of digital art. As time went on and styles evolved and Games Workshops art department grew in size and salary, things have become.. sleeker. That’s not to say that there aren’t still elements of grim darkness to be found in this modern era. There’s a good deal of it, actually – and much of it is bleak, evocative and heart-stoppingly vast in a manner that the older, hand drawn artwork could never have dreamed of.

Still, even some of the most faithful works in this modern era of digital art can’t quite capture the X factor of Warhammer at the turn of 000.M32 – the most obvious and compelling example of which, in my opinion, is Mordheim.

Released in 1999, Mordheim was a skirmish game set in the Warhammer Fantasy universe. Sort of like the Fantasy equivalent to 40K’s Necromunda setting, the premise was that the city of Mordheim was hit by a giant twin-tailed comet formed of ‘wyrdstone’. Other than decimating the city, the wreckage of the comet – wyrdstone being literally warpstone – drew a lot of Chaos attention, particularly from the Skaven who use the stuff for everything from powering industry to recreational substance abuse. Eventually though, various factions – everything from Middenheimers to Vampire Counts – realise this wrydstone has it’s uses and that there is a tidy sum to be made from pillaging the City of the Damned. The ensuing conflict between these small warbands of scavengers forms the core of the game.

Mordheim, like all Games Workshop games, had it’s fair share of problems but on the whole is fondly remembered as a really good game. As with it’s sister system Necromunda, the game was played with a low model count (anywhere from 2-20 models) and a dense table of themed terrain. There was a campaign and progression system that let your models gain experience and level up, gaining stat boosts or new skills and abilities – plus treasure tables and magic items to find. Under ideal circumstances, the game lives somewhere between a hack n slash RPG and a tabletop wargame.

All of this would make Mordheim great, but this is not what made it special. What made Mordheim truly unforgettable to me was how every facet of this game was absolutely dripping with rich, unique aesthetic.

As Warhammer Fantasy before it was more3 than a simple rehash of Tolkien’s Middle-earth, Mordheim was more than just a skirmish game set in the World of Warhammer. It has it’s own flavour and personality – starting from a base of the already atypical Warhammer Fantasy setting, adding a turn-of-the-century historical theme and throwing in an apocalyptic event for good measure. Mordheim is, in a word, nightmarish. The ruined streets are populated with fanatics, doomsayers, mercenaries and madmen – and those are just the Humans. The rest of the population is made up of shambling undead, rat-men assassins, mutant followers of malevolent gods and cut-throats for hire. It frequently evokes images of pyres, gallows and stakes. Of freaks, of fearmongers and Witch Hunters.

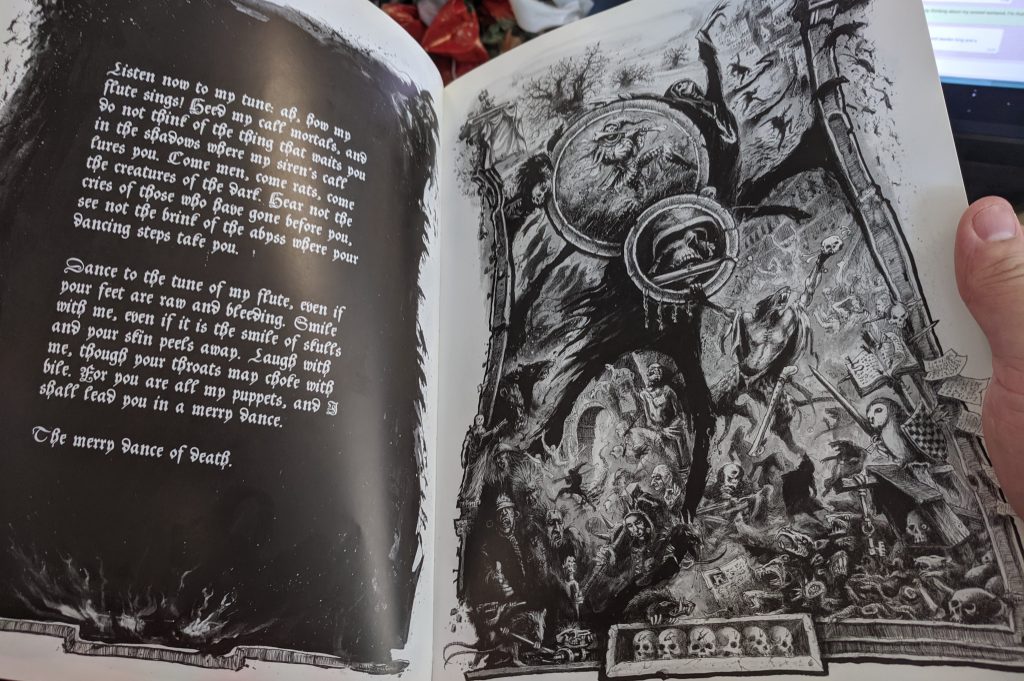

Should the lore alone fail to convey the tone of Mordheim adequately, then the art produced for this game – overseen by the irreplaceable John Blanche – most certainly will.

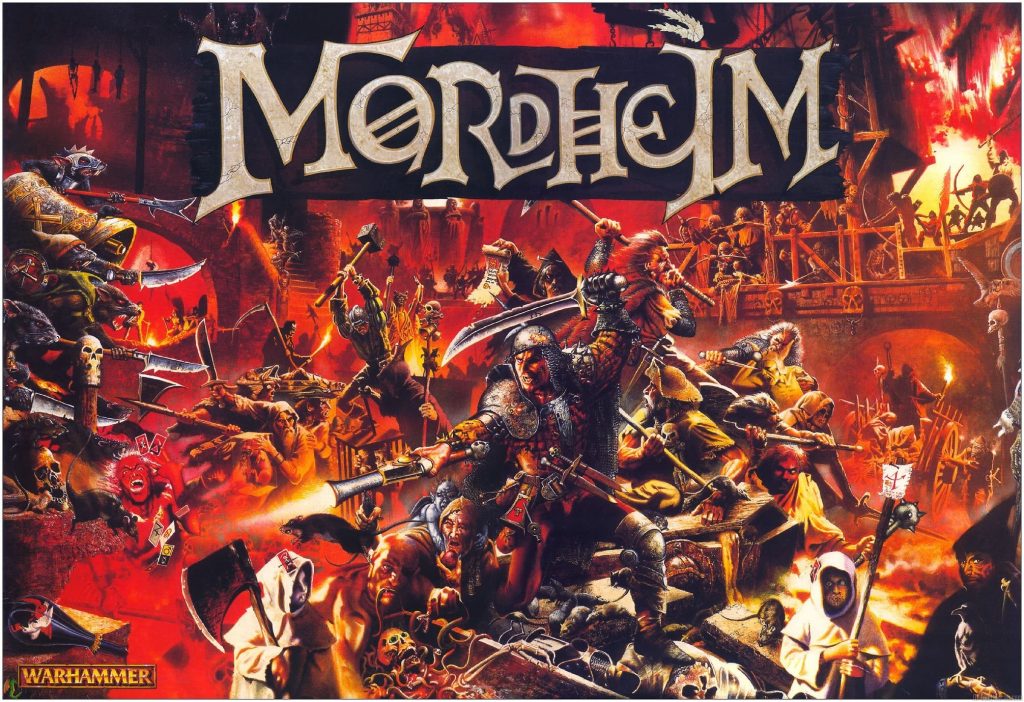

Take the box art (displayed above). On the face of it, it’s a chaotic scene depicting grim looking men fighting for their lives atop a pile of coffins, besset by encroaching rat men. The presence of so many torches suggest that the fight is happening under the cover of darkness, yet the prevalence of reds and oranges suggests that the scene is ablaze with the light from fire and the muzzle flare from blackpowder weapons. It’s claustrophobic, loud and oppressive.

But then, you look a little closer. You start to take in all the little details – the scattered tarot cards; the robed, axe bearing children with stitched lips; the old man with the pig encased in glass; the Cherub-esque imp hanging around one poor souls neck; the creepy shadow man with a crow. Beyond these most extreme examples, there so many interesting little details to take in – from the pained expressions of some individuals, to exotic looking helmets and equipment in play. It’s a bona fide Where’s Wally? of weirdos and oddballs set amongst this gritty, realistic looking battle. The effect? Madness. It feels as if madness has overcome Mordheim, as if all hope is lost.

It just looks really.. intriguing. There is so much to take in and so many questions raised, albeit none you’d like to hear the answer to. It’s as fascinating as it is grotesque, as compelling as it is nihilistic.

This is – to my mind – was the unique X factor that Games Workshop possessed at the turn of the millennium. It was more than simply the ability to bring several influences together into something greater – but that they did so in their own unpredictable and creative voice. There is so much inventiveness packaged into every millimetre of Mordheim, so many fascinating concepts and approaches. The art may venture anywhere from sinister twists on folklore tropes to the manic scrawlings of a madman. The art can be morbid, disturbing, unsettling – but never loses that creative spark that makes everything so, well.. fun. The rulebook reads like a love letter to this setting that was created, and there is joy and passion across every page of the Mordheim rulebook – the sort of joy you only get when you letting artists stretch their creative legs and really go nuts.

But for all it’s eccentricities, for all that the subject matter varies wildly in concept and subgenre – every piece manages to remain cohesive. The style feels defined. Complete, even. Every sketch, every storyboard, every sinister poem and character quote manages to come together and feel like it’s truly a part of the greater aesthetic of Mordheim.

So, I’d be stupid not to make a warband for this 20 year old game, right?

Right?

In practical terms, my descent into Mordheim began a little after the release of Warcry. It’d be a lie to say that I didn’t have my head turned by the game. There was much of interest – the portable, coffee-table sized play area, the awesome looking terrain, the added element of beasts and the beautiful new miniatures. On top of everything, the game dropped just as I was finishing up a number of big projects – not long prior, I’d finally hit the coveted 10,000 points of Space Wolves; I’d managed to tie off the loose ends of my Iron Warriors and finish off a slow-burning Iron Hills project for Middle-earth SBG. I had an opening.

And yet, the biggest selling point of Warcry to me – the immense and functionally complete experience of the starter box – ended up being the single biggest discouragement for me. Warcry, despite being itself a low-model-count skirmish game, was no small project. The starter box included over 30 different miniatures alongside a hefty amount of highly detailed plastic terrain to build, paint, store and transport. Frankly, the longer I considered it as a diversion, the more it became apparent that this boxed game would take just as long to finish as Blackstone Fortress. Quite simply, I didn’t have room in my life for another big project to put off. I passed on Warcry in the end, and went back to finishing off the last bits and pieces needed for my Fellowship of the Ring narrative campaign. But the idea of painting up a skirmish warband as my next project was really in my head.

Around that time, a certain Kickstarter campaign was picking up steam, and managed to grabbed my attention. The project in question was for a range of printed card terrain that could be assembled and disassembled with plastic compression clips. I came across this set linked on the Facebook page for the Great British Hobbit league – and it was love at first sight. Unlike your usual cheap and nasty approach to cardboard terrain kits, the terrain appeared to be printed on thick, coloured card – meaning that the edges matched the colour of the print. Brown edges over wooden panels, for example – as opposed to the usual exposed paper edges (EDIT: I have since confirmed that this was not actually the case. The terrain will have white edges like any other, and the coloured edges were hand inked for the display images. Still a nice kit, but this was not mentioned anywhere on the Kickstarter and leaves something of a bitter taste). Combined with a ‘hand-painted’ aesthetic – as opposed to a more photorealistic approach often employed in kits such as these – really helped set the kit apart. It looked like more than just ‘cardboard’ terrain – it looked every bit as good as any plastic kit I’d ever seen, and miles ahead of a lot of MDF kits to boot. The asking price was very reasonable, and it didn’t hurt that it required very little painting and ‘assembly’ on my part either4. I had to have it.

While I told myself at the time that I would largely be using this terrain for games of Middle-earth SBG – it was via the GBHL Facebook page that I discovered it after all – I must admit that Mordheim was never far from my mind. In my youth, I had very limited experience playing Mordheim – the limited resources of a teenage boy would not extend to building an entire model village to fight over. Still, I’d always quite fancied the notion of a dense table full of multi-levelled terrain to fight over – it’s immersive and impressive to behold. The idea that I could fufil this – whether it be just a city fight game of SBG or a Frostgrave campaign or something. This was all something of a pipe dream at this point, however.

It wasn’t until a couple of months passed since Warcrys release that the idea fully cemented in my head that Games Workshop probably aren’t going to bring back Mordheim any time soon – and if they were, the game might be entirely different. The idea was bandied about a little among some of friends who play The Horus Heresy that maybe we should get into some skirmish game (my suggestions of more people getting into Blood Bowl going largely unheeded), and that maybe Warcry was the play. We thought about it, we discussed it. We discussed what we wanted from Warcry and what it’s shortcomings were. Eventually someone suggested that we just – damn it all – play Mordheim.

Honestly, it just seemed to make sense to me. I loved the setting, and what I knew of the rules felt appealing – and if any group were going to understand the intricacies of Mordheim’s 6th edition rules, it would be the Horus Heresy guys. I remembered that I had a huge amount of Mordheim compatible terrain arriving around February – which a reasonable chunk of time (about 4 months at the time) to get a warband painted without getting too in the way of other life and hobby commitments for everybody.

It felt right. A quick trip to eBay to pick up an old copy of the long out of print rulebook later (though a copy of the living rulebook is available for free online for anybody interested), and here I am.

So, that’s how I wound up getting involved with a 20 year old skirmish game once again. I suppose this whole post could be reduced to “I think it’s cool, and I don’t think there’s a better alternative yet,” but I’m just so dang excited by this game and this project that I felt like I needed to take the time to gush appropriately. Next time, I’m going to get into the nitty gritty of my warband – the conversions, the theme and how I painted them. In the meantime however, I’ll leave you with a group photo of the first batch of kitbashes prior to painting5.

Let me introduce you to ‘The Squeaky Blinders.’

Until next time, thanks for reading, and happy wargaming!

1 I like 8th and Age of Sigmar plenty fine and all, but – as a guy who plays multiple different systems – I really miss 40K and Fantasy being wildly different games with wildly differing aesthetics. Heresy and Middle-earth is kind of the closest thing we have to that kind of dichotomy any more.

2 That’s 2000, assuming I haven’t gotten this wrong and made a complete full of myself…

3 The Old World was rich with it’s own identity. As an example, take the Dwarfs. On the face of it, they’re pretty much the same Dwarves we knew and loved from the works of Tolkien, or what was present in D&D at the time. They’re short and stout, they live underground and love beer and beards. But Games Workshop gave them so much life, history and character that was all of their own. The War of the Beard presented an original take on the classic Dwarf/Elf conflict, while simple cultural things such as rune magic, Slayers, beard growth and the book of grudges brought so much character and inventiveness to the otherwise kind of bland fantasy trope.

4 Thing is, terrain such as such as this – not requiring any painting on my part – is a pretty exciting prospect. Not least because it looks great and will be convenient to use, but because it’s, in a way, a sort of guilt free purchase. It’s the sort of thing you can blow your hobby budget for the month on without worrying about adding yet more things to your backlog. That’s sort of liberating, in a weird way.

5 If you really can’t wait, the models are all over my Instagram and Twitter.